How a major Museum is breaking down barriers between Science and Art

“Enduring Love was actually a novel wishing to oppose the romantic notion that abstraction and logic and rationality and science in particular was a cold-hearted thing, a myth I think which began with Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. We need to reclaim our own sense of the full-bloodedness, the warmth of what's rational”.

(Ian McEwan in conversation with Nima Arkani-Hamed)

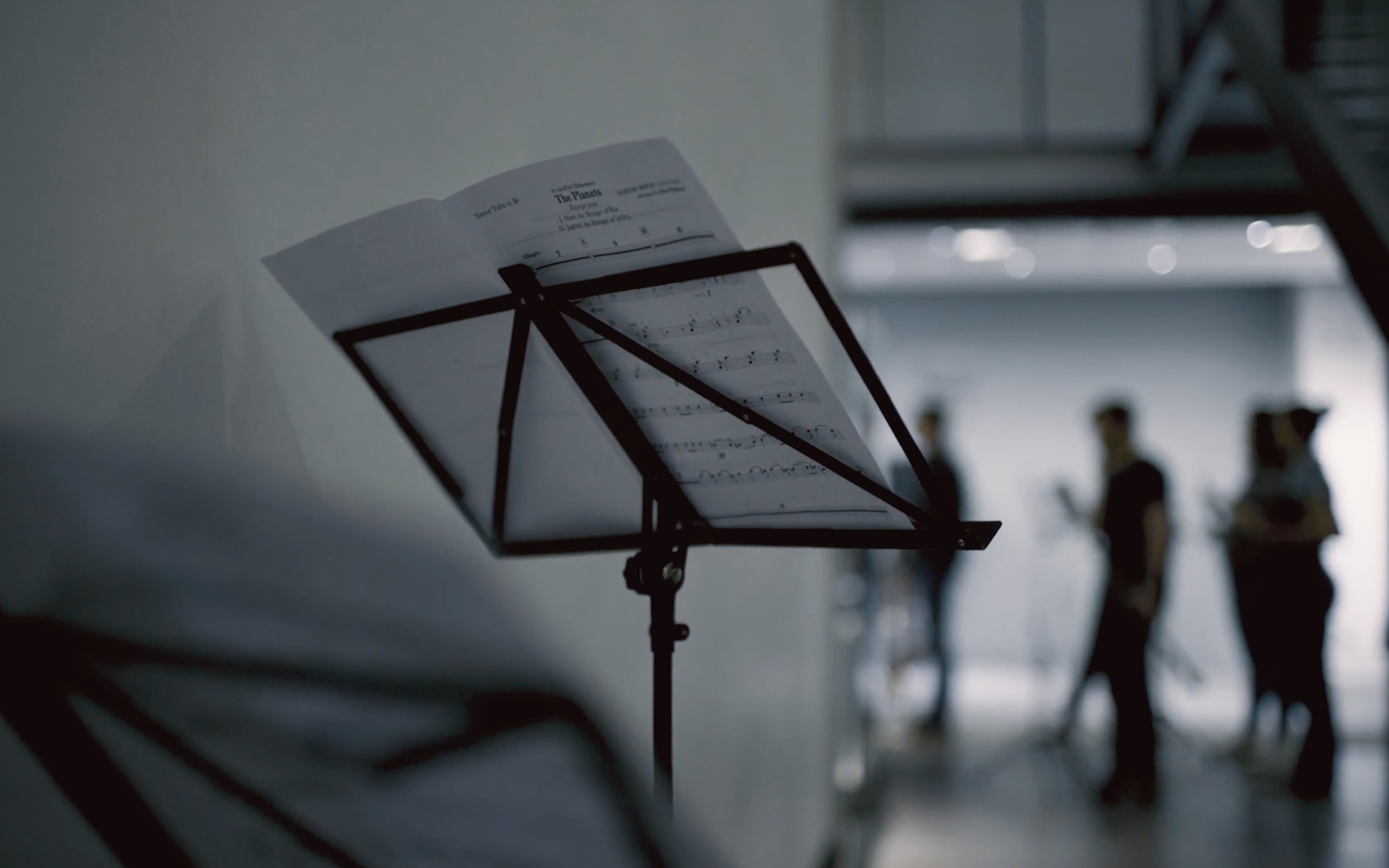

Towards the end of last year Tom O’Leary, Director of Learning at the Science Museum Group, sits down with me to discus a very brave concept he is keen to explore. His plan is to bring the Philharmonic Orchestra of the Royal College of Music into the Making the Modern World gallery - a cathedral like space full of icons - Stephenson’s rocket, Crick and Watsons DNA model, the command module from Apollo 10, Babbage’s Difference Engine to name but a few - and have them perform two of the best loved movements from Holst’s Planet Suite. This would be a surprise performance. A pop up orchestra, if you like. I was lucky enough to be in a position to kick around some ways we could turn this into a film.

Tom’s idea is part of a broader desire to end the divisive thinking around the Sciences and the Arts. Both are often seen as polar opposites but as the artist and neuroscientist Dr. Alan Rorie points out: “They are the two great modes of human thought, both pushing the boundaries of what we know and how we know it; what we can perceive and how we perceive it”.

Today there are encouraging signs that innovators and trailblazers are becoming frustrated at the phony divide between the two disciplines. The cool unemotional rationality of science. The emotive and romantic expressiveness of art. And although science and engineering are not often thought of as beautiful that’s changing too.

In 2013 the Science Museum staged a fascinating conversation between the novelist Ian McEwan and the theoretical physicist Nima Arkani-Hamed. At one point the novelist recalls the famous remark Rosalind Franklin made in 1953 when she saw Crick's model of a DNA molecule for the first time: “that it was too beautiful not to be true”.

In response the physicist recalls a lecture given by Leonard Bernstein about Beethoven. Bernstein is talking about the great composers struggle with the opening movement of the 5th Symphony. How to nail it. And notes that Bernstein when describing this struggle “used precisely the same language we use in mathematics and theoretical physics to describe our sense of aesthetics and beauty”. Anyway I’m on board. There’s beauty in Science. In Design. In Mathematics. In Technology.

Jump cut to a few months later. The gallery is full of school children, teachers, parents and tourists. Then suddenly an urgent drumbeat punctures the murmur of footsteps and chitchat. It’s beginning. Violinists emerge from the shadows. The horns leave a lift. Covers are taken off the harps. The conductor Ben Palmer steps on to the podium and the dramatic shock and awe of Mars – the bringer of war – rises in volume and intensity. The public, already in the gallery, are now surrounded by a 90-piece orchestra. This manouvre, worthy of Napoleon, and practiced in detail the night before, is a tour de force. Two minutes later the orchestra moves seamlessly onto Jupiter and the lyrical theme loved by so many.

If you were standing there you couldn’t help but be moved by the emotional force of the music – powerful romantic and emotive – but also by the context. This music, at this time, in this place, in a gallery brimming with extraordinary exhibits representing some of the greatest achievements of mankind in transport, medicine, physics, technology and computing.

So what about the film? What could a video bring to this union? Well, to begin with, video, of course, lies at the precise meeting point of Art and Science. It’s a visceral medium, great at connecting on an emotional level through pictures and sound. At the same time it’s a medium that employs a daunting array of kit that could easily be shown at a Science Museum. Maybe this museum. In this gallery. At some point in the future.

But there’s something else too. Video is synonymous with story. Filmmakers, sitting down on the first day of an edit, have a number of agonising choices in front of them. Where do I start? How do I tell this story? How do I get to the truth? Because at the end of the day, whether we are Beethoven confronting the 5th or a neuroscientist struggling with the unknown, we are all trying to communicate the truth as we see it.

Our final video is the result of the conversations and the thinking that went into telling this particular story. How many performances should we film to make sure we’ve got it? How do we film the exhibits – grab shots during the performance or shoot overnight when the museum’s empty, allowing us to create the gliding movement we’re seeing in our heads? It’s also the result of many days in the edit suite, turning over the options, working through a multitude of choices in order to weave together these elements. The seamless - I hope - look of the video is the result of careful planning and creative discussion in partnership with the Science Museum, the Royal College of Music and the Director David Betteridge way before the actual shoot.

Anyway, lets leave the last word to a scientist. Here’s Nima Arkani-Hamed again, talking about the quest for story and truth that every scientist goes through:

“I've always thought composers and novelists are probably very close to mathematicians and theoretical physicists psychologically in how they go about things. Perhaps contrary to a certain sort of mythology people don't go to their offices and just churn through equations. You have a certain set of questions you are trying to solve and you have to imagine what the story could possibly be for what the solution is. You have to try to imagine what the sort of global answer could possibly look like – or at least chunks of the global answer. You try on stories – could it work like that? And often because of the underlying rigidity, the same thing that gives rise to the beauty that we talked about, it's beauty because there is a right and wrong. There is some problem that's being solved. If the story is a great story it has a better chance of being right than if it's a crappy story. And sometimes stories are too good to be true and that happens very often. And we try out what could possibly be solutions to the problems and then we have to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as we possibly can. And that's what 99% of our life is about. We try out stories and we prove them wrong”

I can’t remember to be honest the number of cuts we did to get this story right. Through a great deal of hard work, inspiration and the invaluable input from the Science Museum and the RCM we arrived at a cut that I hope does justice to a remarkable event at a singular location. Please take a look.